PART 3: STABILIZING THE FUNCTIONAL RANGE

In parts one and two of this blog series I reviewed lumbopelvic movement, the pelvic tilt, and how to make it work for you. Here in the third installment, I will discuss stabilizing the functional range. We will review core anatomy, and I will address the ever-present debate of abdominal drawing in/hollowing vs abdominal bracing.

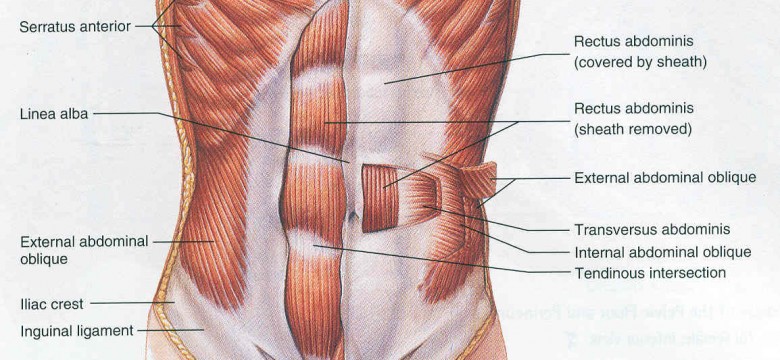

Core anatomy is made up of three main layers which are all intertwined with the thoracolumbar fascia (a layer of connective tissue that frames all the muscles). For the trunk, our superficial layer is comprised of the rectus abdominus (6 pack abs). The intermediate layer includes the internal and external obliques. The deep layer is the Transversus abdominis or TrA. For our spine, our superficial layer is the erector spinae group (not shown in pictures). The intermediate layer is comprised of the semispinalis, multifidi, and rotatores. The deep layer of the spine is comprised of the interspinales and the intertransversarii.

Why is all this anatomy important? It helps you understand the next point of compression/loading and shear forces. Compression or loading forces are forces exerted against an object that causes it to become squeezed, squashed, or compacted. Shear forces are forces acting in a direction parallel to a surface or to a planar cross section of a body (think one vertebra sliding forward on top of the other). Proper understanding of the musculature will help you understand how to withstand more compression and shear forces, ultimately leading to increased tolerance, increased strength, and increased athletic performance. Larger muscles will contribute more compression to the spine and trunk, while not being able to resist shear forces as easily. As you add more compression, you will need increased resistance against shear forces (think pushing straight down on a straw how it bows out to the side). This is because the larger muscles span a greater distance and don’t attach to as many vertebrae or trunk landmarks as the smaller muscles do. Conversely, smaller muscles will better resist against shear force and will not add as much compression to the spine/trunk. Here is a breakdown of the distance each muscle spans:

- Erector spinae group and rectus abdominus (superficial layers): greater than 6 vertebrae

- External/internal obliques and semispinalis (intermediate layers): 4-6 vertebrae (obliques have no attachments to the vertebrae themselves, but if you superimposed the obliques they would span about that distance)

- Multifidi (intermediate layer): 2-4 vertebrae

- Rotatores (intermediate layer): 1-2 vertebrae

- Transversus abdominis (deep layer): attached to the thoracolumbar fascia which attaches to each vertebra

- Interspinales and intertransversarii (deep layer): only run between two adjacent vertebra

Now that we have some anatomy covered, let’s transition into the bracing vs hollowing/drawing in debate. Stu McGill, the world’s leading expert on spinal biomechanics, supports abdominal bracing which is the contraction of all core musculature to increase trunk and spinal stiffness (think preparing to get punched in the stomach). The drawing in/hollowing maneuver is the “isolated activation” of the TrA which will cause your navel to draw in towards your spine. In short, both have pros and cons as most things in life. The bracing will add more compression, but make you more stable. The drawing in maneuver, adds much less compression, but does not make you as stable. While McGill supports the bracing technique, he does recognize the need for individuality when selecting exercises, “Each individual has a loading tolerance which, when exceeded, will cause pain and ultimately tissue damage. For example, a client may tolerate a ‘‘birddog’’ extension posture, but not a ‘‘superman’’ extension over a gym ball, which imposes twice the compressive load on the lumbar spine. For a more highly trained person with a higher tolerance, they may find ‘‘supermans’’ very appropriate. A person’s capacity is the cumulative work that he or she can perform before pain or troubles begin.” This is the cornerstone of how you decide what is best for you.

My personal stance is that it is best to understand and utilize both methods. I would say I am in the middle of the two sides. I do start by teaching the drawing in/hollowing maneuver, but I do NOT emphasize trying to isolate the TrA. Rather, I teach it and discuss how to contract the intermediate and deep layers without the superficial layers (essentially gentle bracing). The more you draw in/brace, the more co-contraction you will get along with more activation of ALL the layers. Depending on the task you may not need the highest level of spinal and trunk stiffness; for instance, bending over to pick up your pen that you dropped on the floor. Conversely, if you are trying to set the world record deadlift or snatch, then you better be as stiff as you possibly can. Some people may disagree and ask why you would teach your body two different movement/activation patterns. The answer is two-fold. First, when completing the drawing in maneuver for the TrA you WILL get co-contraction of the deep and intermediate lumbar stabilizers (rotatores, multifidi, interspinalis, intertransversarii). Ultimately, this translates to the fact that it is almost impossible to isolate your TrA. So while you may not be activating the rectus and spinal extensors a great deal, you are not creating two different activation patterns. Think of the activation pattern as layers and the more stiffness you need the more layers get involved. Second, it piggy-backs of McGill’s quote about loading tolerance, just extrapolated to a full day’s worth of activity and not just a single task. If you were to brace completely every time you dropped your pen, tied your shoe, got bread out of the bread drawer, picked up the dog leash, then by the end of the day you would have accrued a much higher total compression force than someone who did not brace completely during these smaller tasks. Evaluating what the day has in store for you will help you determine how much or little stability you need for all individual tasks. If someone has back pain, then the drawing in maneuver may be more beneficial because they can learn part of the activation sequence without adding to much compression related to their tolerance level. Now if someone has no back pain and just needs more stability, I will spend 5 minutes teaching the drawing in/hollowing maneuver as a foundation then move on to the higher level bracing for increased overall spine/trunk stiffness. Unlike strength and conditioning, I believe generating enough core stiffness to meet the demands of the task will save a lot of stress on your back. In strength and conditioning, powerlifting/oly lifting specifically, we want to move the bar with max force and max speed every rep to drive positive adaptations. Taking that mindset into every daily task, I believe will lead you down a tough path.

Now don’t forget what we talked about in parts 1 and 2 (HYPERLINK). You have to explore the functional range to find the optimal spot. After you find the optimal spot, you need to gently brace or fully brace depending on the task. To teach the gentle bracing, I have my clients in the hook-lying position. From here, take your pointer fingers and find the most prominent bump of your pelvic bones on either side aka ASIS (anterior superior iliac spine). Generally (very general) this will be about 2-3 inches below you navel and roughly 4-6 inches away from the midline. Once you find the ASIS, take your fingers and go 1.5” towards the middle on both sides and press down GENTLY. Right now you should just feel soft, relaxed tissue. Next, bring you navel down towards your spine or the table/floor. You should feel the tissue beneath your fingers firm up a little bit and your fingers might actually sink even lower. This is gentle bracing. Relax everything then bear down like you are going to cough. You should feel the tissue beneath your finger firm up a lot and will likely raise a little. This is full bracing. Feeling the difference between the two is a great way to increase awareness and control (another benefit to utilizing both drawing in and bracing). For the foundation, you should start with working the gentle bracing while keeping proper breathing rhythm. Find the optimal spot via the pelvic tilt, gently brace so you can feel the tissue firm up a little (but not push your fingers up like full bracing), and take 2-4 breaths all while the muscles stay firm. Relax everything and repeat 20-30x. This should not cause any pain; if it is, adjust your position as you may be slightly off of optimal positioning. If you do that and it is still painful, draw in more gently. If after that it remains painful, switch to side lying and repeat the same process. It is very important that you can feel the firmness of the tissue, both with your fingers and paying attention to how it feels internally (just thinking about it). If you don’t know what you are feeling, relax everything and compare the soft relaxed tissue to the DIFFERENCE in the tissue when you complete the maneuver. If there is no difference, you need to draw in/brace a little more. If it pushes your fingers up then you are bracing too much and need to be gentler with it. The understanding and awareness of what you are doing is the real key here, not whether you get it “right or wrong.” If you are trying to gently brace and it pushes your fingers up (fully brace) then as long as you know you did something that you were not going for, that is a success. Of course after you do this for a day or two, I want you to be able to do what you are going for. If you want to fully brace, make sure you fully brace. If you want to gently brace, then make sure you only gently brace. Do it as many times as you need until you can breathe without losing the activation and you can successfully do what you are attempting to (full vs gentle brace). These techniques help hold your spine and trunk in YOUR optimal position. The next step is to start adding movement on top of the stability. The more challenging the movement, the more challenging the work is for your core. This will be discussed in the fourth installment.

Managing the stresses placed on your back and trunk throughout the day is the key to long term back health. Understanding lumbopelvic movement, the pelvic tilt, and appropriated stabilization strategies helps you manage that stress. The transfer of these strategies to EVERY SINGLE daily movement tasks, no matter how big or small, will keep your back effective and very efficient. Check back for the next installment which I will talk about integration to common daily tasks and how to decide to use the drawing in maneuver or bracing technique. Following that installment, I will discuss how to select and progress therapeutic exercises to improve your activation and stabilization abilities. Finally in the coming weeks I will reveal how we can leverage all of this knowledge for heavy strength and conditioning and athletic performance.

References

- Dionne, C. (2015). How are we still getting it wrong: Abdominal hollowing vs. bracing. Retrieved 3/19, 2016, from http://breakingmuscle.com/mobility-recovery/how-are-we-still-getting-it-wrong-abdominal-hollowing-vs-bracing

- McGill, S. (2010). Core training: Evidence translating to better performance and injury prevention. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 32(3), 33-46.

- Vera- Garcia, J., Elvira J, Brown, S., & McGill S. (2007). Effects of abdominal stabilization manoeuvres on the control of spine motion and stability against sudden trunk perturbations. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 17, 556-567.